The automotive industry is speeding towards a collision with the future.

EPA recently installed new vehicle emissions standards that can be met if 56 percent of passenger cars are electric by 2032. Meeting the standards will require a significant increase in sales of electric vehicles. Twelve states already promise to withdraw sales of new gas-powered vehicles.

America may have difficulty making the transition to electricity. The number of electric cars on the road is increasing rapidly, making up 6.5 percent of new car sales, but it’s still just that. 1 percent of all registered vehicles. For more than a century we have relied on gas-powered piston engines for our personal transportation. Only a few alternatives have been tried.

In the 1970s, Mazda introduced the Wankel rotary engine, which used a rotating, triangular rotor that acted as a single piston. It was a clever concept, but it had low fuel efficiency and high emissions, and it still relied on gasoline for ignition.

Only once, it seems, did a Big Three automaker seriously explore an entirely new area in automotive engines. It took place in 1962, the year of light cars, according to Arthur Baum, the Post it‘s automotive editor, who thought the automotive industry was settled in a rut. There was some excitement when they started making small, fuel-efficient cars like the Ford Falcon and Dodge Dart. Before their arrival, heavy vehicles were involved 95 percent of car sales.

Now, in 1962, the gas-guzzling behemoth continued to account for only 56 percent of sales (and it would drop to 35 percent by 1973).

But Detroit was taking a few chances. The ’62 models were limited. The Corvair and Volkswagen had pioneered the rear engine design. The Pontiac Hurricane had a rear end transmission. All cars were based on an internal combustion, identical engine. There was little to excite Baum’s interest.

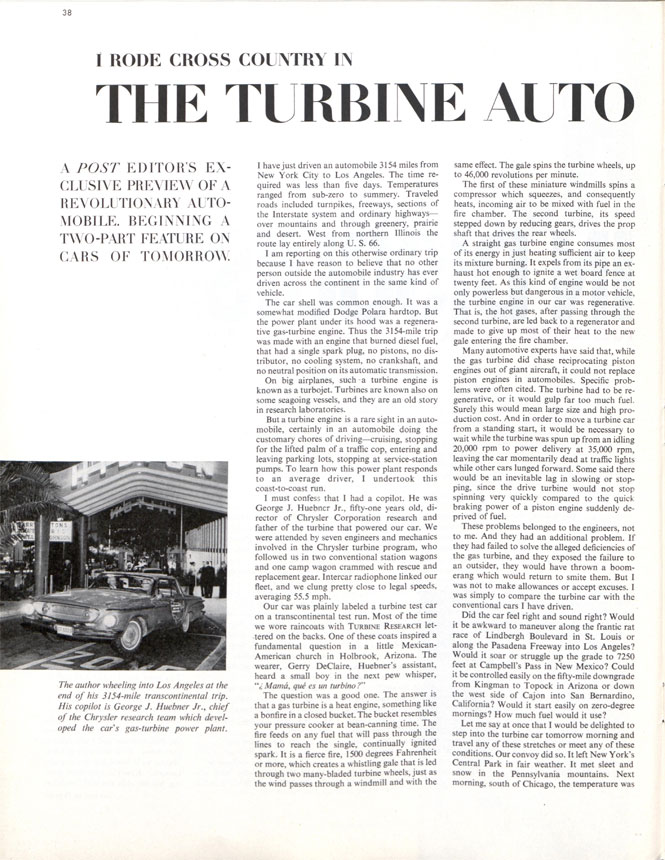

So, when he was offered the chance to ride coast to coast in one of the greatest inventions in automotive history, he jumped at the chance.

The innovation was an entirely new engine: the Chrysler Turbine.

Turbine engines were common on airplanes, but there had been little effort to fit one into a car. It was assumed that they would be too big, too expensive, and too unresponsive to traffic.

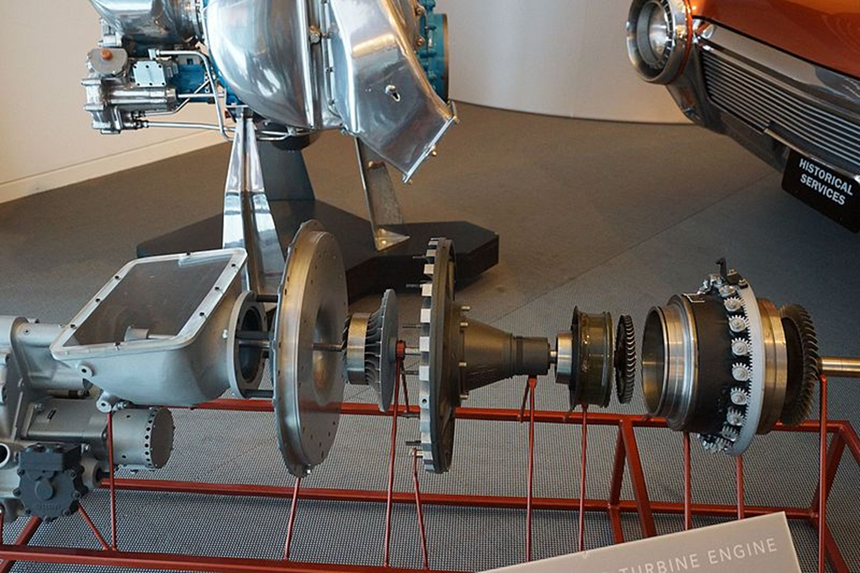

But Chrysler had developed an engine that tried to overcome these objections. Its CR2A turbo engine had no pistons, distributor, cooling system, or crankshaft, used only a single spark plug, and could run on a variety of gasoline chemicals, soybean oil, or even perfumes.

How It Worked

A turbine is an engine driven by heat. Instead of a gas-air mixture burning in a cylinder to drive a piston, a turbine collects air, heats it, and mixes it with fuel. This mixture returns to the area where it is heated to 1500 degrees Fahrenheit and forces the air back over the turbine fan blades, turning them at speeds of up to 46,000 rpm. This is connected, through a transmission, to the wheels.

One of the limitations of turbine engines is the amount of heat they generate. Exhaust from a turbine engine could ignite a wet, wooden fence 20 feet away. But the CR2A cooled its exhaust by returning it to the combustion chamber.

In early 1962, Baum climbed into a turbocharged Dodge Polara in New York to begin his cross-country journey. He was surprised by the lack of vibration while the car was idling. And as the hours ticked by, he was pleased with how much fuel the car was getting. Using only diesel fuel, it got 16.6 miles per gallon — admittedly poor mileage by today’s standards, but better than Chrysler’s regular sedans. (In 1962, the average car mileage was 12.4 mpg.)

Baum listed other advantages of the Chrysler CR2A engine. For one thing, it was easy. It had 200 parts less than a piston engine and was half the weight. It requires no oil changes and little maintenance. And its exhaust had no hydrocarbons.

The turbine went very well. There was no fault in the system for the entire length of the journey. And the car easily drove up the road to the Continental Divide while the accompanying sedans had to get off.

But, as you might expect for a design that never found the market, major problems remained. For example, a lag during acceleration (“spin-up lag”) was observed. When starting from idle, the turbine had to be moved from 20,000 rpm to the power supply at 35,000 rpm, leaving the car momentarily dead at traffic lights while other cars shot ahead. There will also be a lag in reducing or stopping. The drive turbine did not have the stopping power of a piston engine suddenly deprived of oil.

In the old prototypes, the spin lag was as long as six seconds. Chrysler’s Turbine had reduced the delay to 1.5 seconds (still enough for the driver behind you to honk).

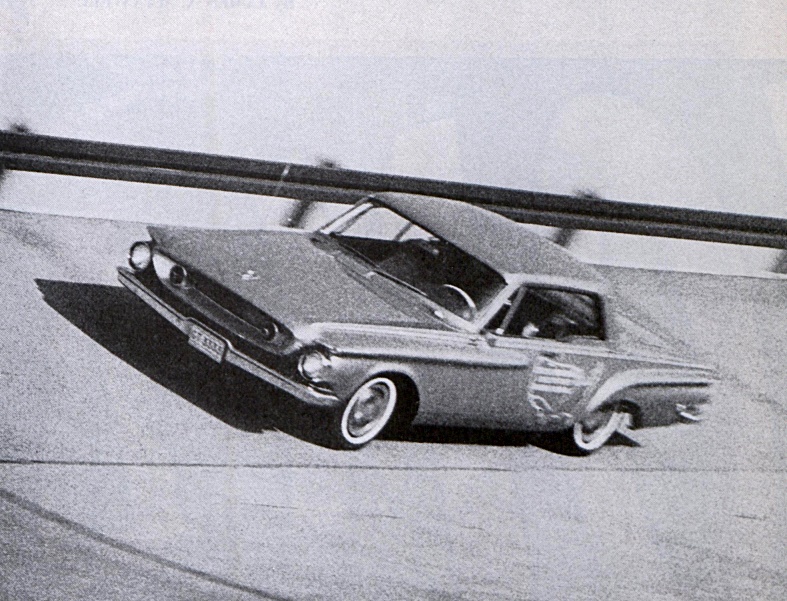

Chrysler seemed to be very focused on turbo cars. It showed several of these cars at the 1962 Chicago Auto Show, and built fifty of them, all in eye-catching bronze, which it lent out free to the public. More than 200 drivers took advantage of the offer.

The body featured an Italian-influenced design that deliberately evoked the “aircraft age” (which came before the “space age”), and the high-pitched sound of the engine resembled an airplane taking off.

Chrysler continued to work on the engine, releasing the fifth and sixth generations. But they could not meet the government regulations. The Department of Commerce, which was helping finance development, concluded that the machines were not suitable for cars. In the seventh generation turbine, it became clear that the engine would not meet fuel economy goals.

The turbine program ended in 1966. Forty-six of the cars were recalled and destroyed, which was standard practice in the automotive industry for prototypes. The Nine Plants are all that is left of the attempted revolution.

The transition from internal combustion to electric promises to be a major challenge for automakers. But there is room for hope among people who once fit the jet engine inside the Dodge Polara.

Become a member of the Saturday Evening Post and enjoy unlimited access.

Register now